Technological Revolutions and Art History, Part Three: Toussaint Nothias

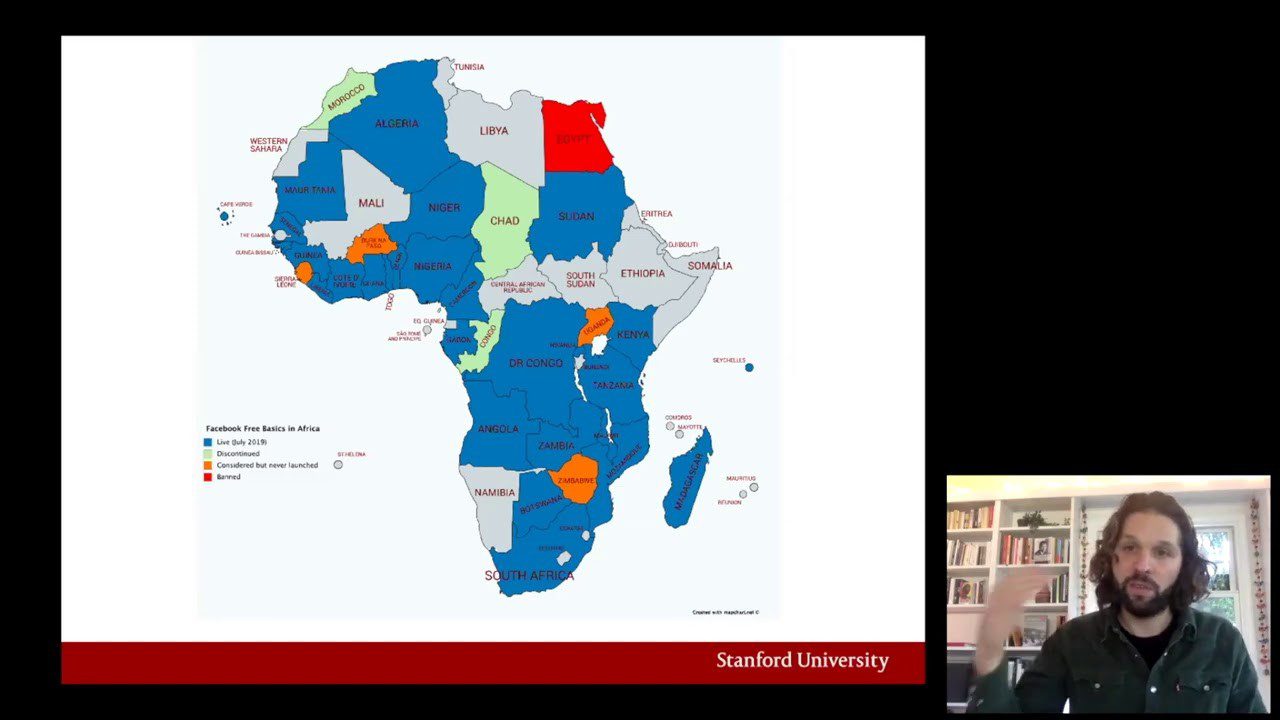

“Access for whom, access to what? African Cultures in the Corporate Digital Enclave”

Toussaint Nothias, Stanford University

In a context of widely unequal digital access worldwide, many tech corporations have invested in a range of projects to increase connectivity. In this talk, I focus on one of the most prominent of these initiatives across the African continent: Facebook’s Free Basics. By exploring its expansion, its impact on local media production, and its reception by local communities, I offer a critical examination of these types of initiatives and their relevance to cultural heritage. Following the lead of other scholars and activists opposing “digital colonialism,” I relocate this phenomenon within a broader history of inequalities pervading global knowledge production in fields as diverse as art history and computer science.

Historically, science and the humanities were not considered two discrete disciplines: the separation of these two branches of knowledge developed only in the modern era. For art historians in the twenty-first century, this divide is only widening as some scholars embrace technological advances while others remain unconvinced that computational techniques and tools can bring meaningful changes to the field. Like the previous symposium “Searching Through Seeing: Optimizing Computer Vision Technology for the Arts” hosted by the Library in 2018, this four-part event seeks to encourage art historians to connect with the computer sciences by exploring the role that technology has played in the development of the discipline of art history and providing an opportunity for conversation and the exchange of ideas.

Presentations in Part III of the symposium will explore the ethics of digitization and how issues regarding access and discoverability impact research in art history. Speakers will critically examine how technologies, from 3D modelling to artificial intelligence, have the potential to expand audience engagement with cultural heritage institutions and their collections yet also, ironically, limit understanding and community connection by omitting context, introducing bias and legal restrictions, and problematizing concepts of ownership and authenticity.